By Inger Morthorst Møller, on behalf of DanBred.

Vaccines are extremely important aids for preventing diseases and the economic losses associated with disease outbreaks in modern pig production. It is though important to understand that vaccines and vaccination programmes must be carefully planned and professionally handled with attention and precision to achieve the full benefit.

The article will describe the background for vaccinations and how this is best handled also in the unlikely event that a mistake happens.

What is a vaccine?

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease. Thus, vaccines contain a bacterium, virus or most often parts of this along with a so-called adjuvant. The adjuvant is an excipient that will help activate the immune system to aware the body of a stranger has entered. These are the same defence mechanisms initiated if the body is met by a natural infection. Hence, vaccination triggers the body to induce a beneficial immune response.

In domestic animals, most vaccines will be given twice. The first vaccination will awaken the immune system and the second vaccination will alert the immune system that this infection occurs repeatedly and why the body will start to build a defence against this stranger, ie initiate production of antibodies. The ideal gap between two vaccinations is approx 2-3 weeks. This will let the reaction to the first vaccination subside before the second vaccination is given. However, some vaccines are designed as one-shot vaccines, why these should only be given once to achieve the full response. Due to the small amount, or in some cases only part of bacteria/virus in the vaccine, the animals normally do no exhibit disease. A veterinarian should though always design and approve both the vaccination as well as the vaccination plan before initiating anything.

After vaccination, the antibodies will be present in the bloodstream ready to capture the exact pathogens, for which they are intended. Over time, the antibodies might disappear from the bloodstream why re-vaccination can be necessary to re-build the number of antibodies needed.

Correct vaccination technique and time

Always ensure that the relevant staff have had proper training in vaccine management before initiating any vaccinations. Vaccines should always be given into muscle tissue. Typically vaccines are placed deep in the large neck muscle. The correct place would be approx. a hands-width behind the ear perpendicular to the skin. If the vaccine only reaches fat layers, the immune system will not be stimulated sufficiently and the effect of the vaccine will be limited and in some cases unknown. Therefore, ensure to evaluate the size of the animals before vaccination as the correct size and length of the needle is vital for the effect of the vaccine.

Besides, it is important to always follow the vaccine manufacturer’s recommendations on correct management and time of vaccination, to ensure the full effect as this will assure that the animals will produce a sufficient amount of antibodies before they are exposed to the disease in question.

Disposition is e.g when gilts are moved to the sow herd or when introducing new animals to a herd. It is important to avoid that the gilts become ill when they are moved into the sow herd, but on the other hand, it is also important that the gilts do not introduce new diseases into the existing herd. A Danish study by Sørensen et al. (2015) found that gilts pose a great risk of influenza instability because gilts often carry influenza if moved from the quarantine facilities to soon after vaccination. It is therefore important to ensure a proper quarantine setup, where the gilts can get the basic vaccinations, as well as have tome to develop the proper level of antibodies but also pass the point in time where the gilts do not excrete virus before introduced to the sow herd.

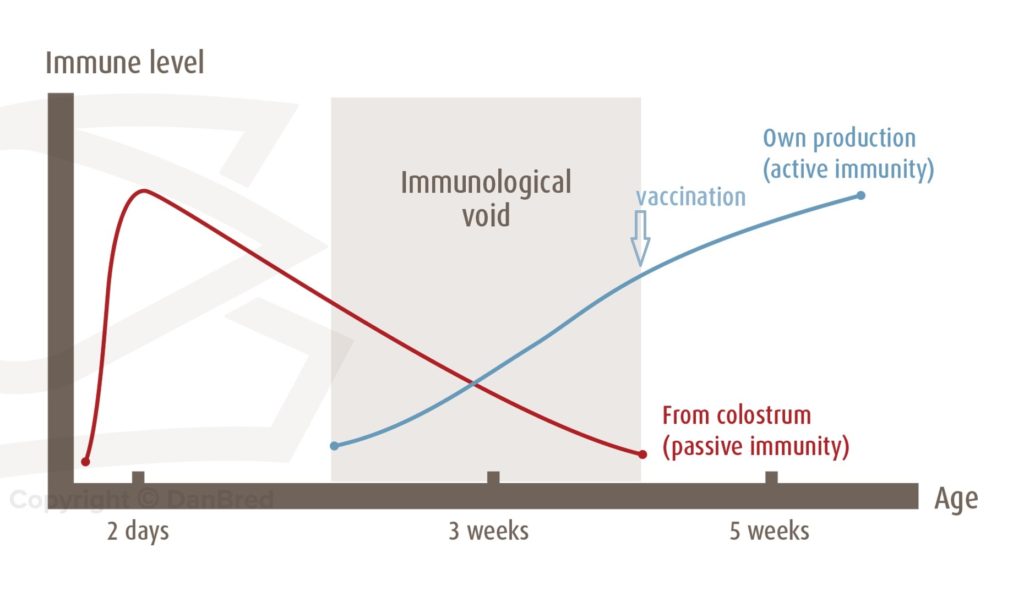

Some vaccines are intended to protect the sow against diseases such as Erysipelas or lung disease, during gestation it can be an advantage to vaccinate the sows to ensure the formation of antibodies which is then transmitted to the newborn piglets via colostrum. As the piglets are born without an immune system, these antibodies from the colostrum, called maternal antibodies, will act as a passive immunity for the young piglets. This passive immunity will protect them for the first weeks of their life while their active immunity is building. Vaccinating the piglets during the suckling period or immediately after weaning, will help boost the formation of an active immune system within the piglets. Again, following the vaccine manufacturer’s recommendations is imperative, as a vaccine administered prematurely will not have the intended effect, as the maternal antibodies in the piglet might react and neutralise the vaccine.

It is imperative to administer vaccines for piglets at the right age to ensure the full effect and avoid the antibodies from the passive immunity suppress the vaccine.

Achieving good efficient immunity among gilts can be a challenge. An immature immune system often manifests it selves as diarrhoea in piglets. Richard et al. (2019) examined if changing vaccination strategy where the vaccination against necrotizing enteritis was given just before insemination instead of the normal recommendation, which is just before farrowing. The change in strategy led to a promising finding of significantly more antibodies in the colostrum and afterwards in the blood of newborn piglets, which could indicate that this strategy could help protect the piglets against disease at the beginning of its life.

Checklist if experiencing a lack of effect

In the unlikely event that the vaccine strategy does not have the expected effect, it is important to do some proper troubleshooting. The following checklist can be used for the identification of issues that can lead to the reduced effect of vaccines.

Delivery and storage

Vaccines for domestic animals should always be stored according to the vaccine manufacturer’s recommendations, this normally means refrigerated at a temperature between 2 – 8 Co.

This applies from the time the vaccine is produced until it is used in the herd. It is important to maintain the refrigeration chain also while moving vaccine doses between different destinations. On the farm, the goal is to get the vaccines refrigerated as soon as possible immediately after delivery. Do not push the vaccines against the back of the fridge, due to the risk of freezing. Ensure that the refrigerator on-farm has an accurate temperature display or a manual temperature gauge that is read frequently.

Improperly stored vaccines can be expensive acquaintance, both because the destroyed vaccines have to be repurchased but especially if an outbreak of disease occurs due to the use of damaged vaccines.

Vaccination technique

Proper training of staff who perform the vaccinations is imperative. The staff must have an understanding of how important the task is and why it must be performed to perfection for every dose administered.

Clean syringes and sharp needles are essential for avoiding the spread of bacteria between the animals. Furthermore, using a sharp needle is to consider animal welfare as it reduces vaccination pain and thereby reducing the risk of incorrect placement of the vaccine.

Should a residue be left in the bottle, it is important to know that this has a very limited shelf life why it either be thrown out or as an alternative immediately used for an animal in the next week batch.

Vaccination time

It is to the extent possible very important that the vaccination has been performed before the animals are exposed to the disease. Ensuring proper registrations, either electronically or on pen boards will be a help for the staff who are in charge of the vaccinations and will ensure that the vaccines are given on time.

Unfortunately, an unexpected disease can occur and an expected disease appear earlier than anticipated. In the last case, it is important to review and adjust the vaccination programme accordingly. Eg. If weaned pigs are vaccinated against E.coli-diarrhea the day after weaning, but still get diarrhoea within the first week after vaccination, then the time of vaccination should be moved back, to ensure piglets can build up the immunity before weaning.

Vaccination of sick animals

If vaccinating clinically ill animals, there is a risk that the desired effect will not show due to the fact that the immune system of the ill animal is actively fighting the disease and therefore, is not able to develop new antibodies based on the vaccine administered. Hence, only healthy animals should be vaccinated to achieve full potential.

Serological examination of the animals

If in doubt whether the vaccination is carried out correctly or have had the full effect, check for antibodies before and after vaccination. This could e.g. be a test for antibodies against parvovirus and/or erysipelas in gilts before and after vaccination.

Assuring health and productivity

Proper execution of vaccinations is a safe and efficient method of preventing economic damage from an infectious disease in your pig herd. Proper preparation, handling and storage are though imperative. Always let the herd veterinarian plan and approve the vaccination programmes and ensure that is professionally handled with attention and precision to achieve the full benefit and in health and productivity.

References

Richard, O.K., Grahofer, A., Nathues, H. et al. Vaccination against Clostridium perfringens type C enteritis in pigs: A field study using an adapted vaccination scheme. Porc Health Manag 5, 20 (2019).

Sørensen, S. S., Guldberg, H., Ryt-Hansen, P., Larsen, L., Larsen, I., & Kristensen, C. S. Polte kan vedligeholde influenzasmitte. SEGES Notat nr. 2015. (2020)