By Lola Kathe Tolstrup, Senior consultant, DVM, PhD, SEGES Danish Pig Research Center, Livestock Innovation.

Abstract

Gilts introduced in the sow herd must preferably have the same or higher health status as the sow population, to which they are being introduced. This is to ensure a match of the immune system capacity in the whole herd. If un-matched there can be disease outbreaks with costly consequences. Even though health status is matched, appropriate quarantine facilities and procedures are necessary to prevent introduction of new diseases into the herd as well as to protect new gilts from severe clinical disease when introduced, and exposed to the different pathogens, in the sow herd. Quarantine must be at least 8-12 weeks to ensure possible disease in the gilts to develop and be discovered. Hereby you can make sure that any vaccination has had the time to activate the immune system. Even though replacement gilts are produced in the same herd as the sow population, a quarantine period for replacements gilts is preferable and your herd veterinarian can be helpful when establishing a gilt introduction plan for your specific herd with a specific health status. Special precautions must be taken when dealing with PRRSV, as most vaccines are live vaccines and vaccinated animals therefore shed virus after vaccination and therefore can infect other susceptible animals in that period. So, compliance of the quarantine period is crucial in case of PRRS vaccination.

Match and mapping health status

Immunity

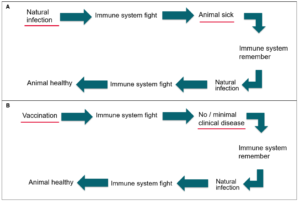

Introducing gilts into the farm can be gilts from own production or gilts bought from an external supplier. In both cases emphasis must be put on the importance of matching the health status of the gilts with the health status of the animals already at the farm. When the immunity of the gilts matches the immunity at the farm, the gilts will be prepared for the possible disease challenges they will meet when entering the farm and hereby enhance the chance of a successful start to their reproductive carrier. This is due to the nature of immunity, where the animal must have met the challenge of disease to fight the following disease without, or with less, clinical signs. This can be accomplished by natural infection or by vaccination (figure 1).

Figure 1: A) immune reaction after natural infection/disease.

B) immune reaction after vaccination. The endpoint in both pathways are the same, but for vaccination the risk of clinical disease (because of the first immune system reaction is reduced).

If animals have not yet met a disease, they are immunologic “naïve”, and thus susceptible to become sick from the infection. It also means that an entire sow herd can be naïve to a disease which is not present or have been present in the herd. Therefore, introducing a single gilt with e.g. a virus for which the sows have no immunity, can result in severe clinical disease in the herd.

Gilts from own production

When introducing gilts from own production, the animals should have met the different pathogens already in the farm and the risk of them introducing new diseases are low. Introducing the gilts through a quarantine stable is preferable but is dependent on the disease status of the farm and the vaccination protocol. The herd veterinarian should be consulted on that issue. Regarding immunization of home-produced gilts, it is important that they follow the vaccination scheme that is necessary for the specific farm, because not all early life accomplished immunity will last until and after the gilts has been introduced into the sow farm. This disease could be, but are not limited to, parvovirus, PRRS and PCV2.

Buying gilts

When buying gilts from an external supplier, focus on health status and immunity is essential. Suppliers with the same or better health status must be chosen to limit the risk of introducing new disease. However, if the animals are introduced from a farm where the gilts

have not met diseases present in your farm, vaccination becomes a crucial issue. A clinical health examination of the gilts should always be performed, but for bought gilts it is even more important, as the exact history of the animals are unknown. The unknown factors can be minimized by securing that the gilts are accompanied by a health and vaccination history when sold.

Mapping health status

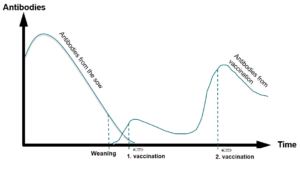

When animals have developed immunity towards a disease, this can be seen by development of antibodies. These antibodies make the immune system capable to detect and fight diseases the animals might meet later in life. Antibodies can be present as either maternally derived antibodies (from sow to piglet), as antibodies developed after vaccination or after natural infection. Furthermore, the number of antibodies can change over time, and therefore it is important to know the disease and vaccination history with a timeline to evaluate the possible immune status of the gilts when introduced (Figure 2).

Figure 2: An example of how antibodies over time can change, depending on the origin of the antibodies (maternal immunity vs. vaccination) and time of vaccination. The pattern of the quantity of antibodies through time depends largely on type of disease and vaccination.

Also, antibodies can be measured from blood samples (and for PRRS in saliva), which means, that beside making a thoroughly examination of the gilts when arriving at the quarantine stable and throughout knowledge of vaccination and disease history, blood samples can be used to establish the immune status of the animals.

Importance of quarantine compliance

Quarantine and immunity

Even though the gilts have an optimal health and vaccination history, and that the clinical examination at arrival is without remarks, diseases may develop later after introduction of the gilts. Also, time needs to follow vaccination to develop prober immunity. Therefore, a quarantine period is essential. Here the gilts can develop the immunity needed before introduction to the sow herd and if any disease was present in the gilts at the arrival, it will, potentially, be discovered before introduction of the animals to the sow herd. The quarantine period should be between 8-12 weeks, as this would ensure time to discover any disease present in the animals and to ensure prober immunity after vaccination [1]. Another important aspect of quarantine facilities is to have the quarantine stable physically separated from the sow facility; preferably on another site, because some disease pathogens can travel through air (e.g. PRRSV and Influenza). Furthermore, if the facilities are at different locations, it will more likely be acknowledged as two different sites and compliance of external biosecurity would be increased.

Quarantine and PRRSV

The quarantine period (12 weeks) is especially important regarding PRRS vaccination with live vaccines or by immunization by introducing a PRRSV excreting animal to the quarantine facility, as the animals will excrete virus after vaccination / receiving the virus up to at least 10 weeks. Hereafter the gilts can be introduced into a stable PRRS-positive herd and the herds remains stable, as they would have developed antibodies like the rest of the sow herd. However, it is crucial to follow the vaccination procedure strictly, and possibly take follow-up blood samples, to secure that every animal develop proper immunity [2].

Quarantine failures

Failure to comply with quarantine procedures can have fatal consequences, as introduction of new diseases to a naïve herd can decrease reproductive performance, increase the antimicrobial use and increase mortality for the entire sow population. On the other hand, introducing naïve gilts to a diseased sow herd, can give problems with relation to gilt replacement as diseased gilts could have difficulties starting the reproductive cycle e.g. with an increase in numbers of re-breedings as a consequence. Therefore, if reproductive problems are seen with the gilts, the issue may originate from the quarantine stable.

References

1. SEGES_Svineproduktion, Manual om repromanagement. 2019, SEGES DANISH Pig Reserch Centre.

2. Hoelstad, B.E., Introduction of replacement gilts to PRRS-positive sow herds, National Veterinary Institute. 2016, DTU.